All children come to Transitional Kindergarten (TK) with different backgrounds, cultures, families, and experiences. Some children may have spent a year or more in high-quality preschool programs, while for others, this is their first day in a classroom and maybe even their first time away from their family. Children may arrive from stable and comfortable backgrounds or may have experienced immigration, homelessness, hunger, or housing instability. Some children in class may be only children who are used to interacting with adults but are overwhelmed by large groups of children, while other children may be accustomed to leading a band of siblings and cousins at home.

Teaching the whole child means recognizing and valuing each child’s unique contributions to the classroom. Some techniques that will help you serve your diverse learners include differentiated instruction, culturally responsive teaching, and trauma-informed practices.

Each student who walks into your TK classroom brings their unique experiences and has their own learning needs and learning pace. An individualized approach is critical to ensuring your students reach their highest potential. As you plan for the individualized and differentiated instruction that addresses the needs of all TK students, you can consider the various strategies, content, and activities that meet their needs across the continuum of learning.

Example strategies for differentiated instruction include:1

Teachers may need to look at breaking skills down into sequential steps and varying:

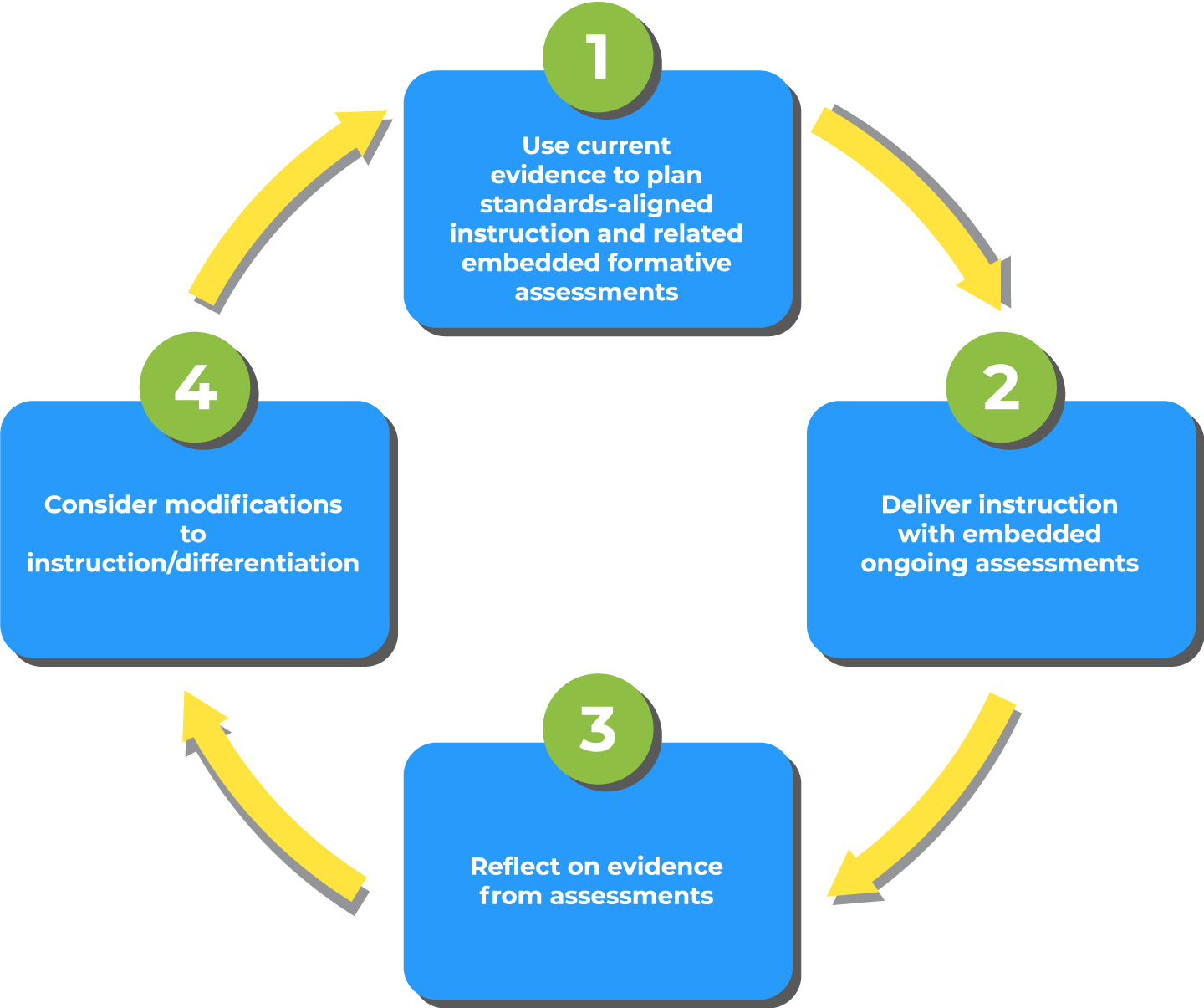

Intentionally using assessment to differentiate instruction will help your young students succeed in TK, and build the strong foundation that will ultimately prepare them for meeting the Kindergarten standards. Evidence from formative assessment leads naturally to differentiated instruction and flexible grouping. Based on evidence from formative assessments, you can meet children where they are, adding just enough challenge so that a task goes a bit beyond what your student can already do.

Differentiated instruction in any classroom can be a challenge without the right planning tools. As TK teachers plan to incorporate differentiated instruction into their daily schedules it may be helpful to remember these key points:

As a TK teacher, you understand the importance of a developmental approach to instruction. TK teachers work to ensure that each child is working in their “zone of proximal development”2 (ZPD). The ZPD is just the right gap between what the child can do independently and what the child is newly learning. Formative assessment provides evidence and guidance in finding the “zone” for each child. The goal of differentiated instruction is to provide scaffolding, or temporary support, to guide children from what they already know to what they can do next.3 Teachers can then gradually remove the scaffolding, reducing the support as the child begins to master the skill and prepares to move on to their next step.

Once you identify the gaps in some students’ understanding, determine that others are right on target, and discover that others might benefit from an additional challenge, the focus becomes deciding what to do next to meet their needs.

Many children need to back up a bit to fill in missing concepts or correct misconceptions in order to move to the next step. As you decide which strategies you will use to scaffold and guide your students to fill in the gaps in their learning, you will be able to get them back on track to meeting their goals.

Differentiated instruction is a critical aspect of meeting the individualized needs of TK and Kindergarten students in a combo classroom. Because TK offers the gift of time, the teacher is able to move through the curriculum at a pace that meets student needs, guiding social development, fine and gross motor skill development, as well as academic development. Students can be flexibly grouped to allow teachers the opportunity to support children to meet specific objectives. These groups are not static and may be reconfigured often, dictated by observation and/or assessment of children’s progress.

Note: The following snapshots assume only one adult is present. If two adults are present, the challenges of providing differentiation are eased somewhat.

TK is the first opportunity to create a school culture that captivates children, inspires them to dream, and supports them to be successful life-long learners. Your TK students enter your classroom with knowledge from their home experiences that can be used to expand their learning. The positive learning outcomes you cultivate in your classroom are exponentially greater when children feel the respect and appreciation you have for the rich cultural capital that their family contributes to the educational environment. Culturally and linguistically responsive and relevant teaching and learning are grounded in educational research which recognizes that “young children learn best in an interactive, relational mode rather than through an education model that focuses on rote instruction.”4 Children deserve to be in an environment where their strengths are nurtured and used to connect them to new knowledge, and their culture and home languages are recognized as essential elements of learning.5

This section offers many research-based suggestions for culturally and linguistically responsive teaching so you can see the best learning results in your students.

Culturally and linguistically responsive relationships with your students contribute significantly to their academic language acquisition. Integrating family participation, through family at-home learning activities, classroom participatory visits, and school volunteerism, allows you to support children’s family relationships and healthy development. Mutually respected, supportive roles create effective partnerships. Co-constructing your learning community with families enables you to create thriving multicultural classroom learning environments. Welcoming and engaging your families as co-educators of their children creates spaces for you to be more creative in curriculum design and integrating children’s cultural and linguistic experiences.

Culturally and linguistically responsive relationships are important for all children but can be especially impactful for Dual Language Learners (DLLs). Teachers can demonstrate respect and excitement about diversity in their classroom by inviting parents or other family members to share food and cultural traditions and by using parents and other volunteers to incorporate children’s home language and culture into the classroom. Teachers should also encourage parents to continue speaking their home language with their children so that they can continue to develop their home language and reap the many benefits of bilingualism.

Culturally and linguistically responsive and relevant teaching and learning create a space in which the teaching and learning relationships build on the strengths of the teacher, child, and family, and where children’s cognitive, social-emotional, and physical development is enthusiastically supported daily. As part of your efforts to work with the experiences and assets your students bring into your TK classroom, you can:

For more information and resources on culturally and linguistically affirming and responsive teaching, visit the Multilingual Learning Toolkit sections on Classroom Environment and Family Engagement.

Approximately one-quarter of all children in the United States experience or witness trauma before the age of four, so it is highly likely that the typical TK teacher will encounter students who have already experienced challenging experiences in their short lives. Examples of trauma include witnessing or experiencing abuse or domestic violence, food scarcity, housing instability, or the sudden absence of a parent or parental figure due to death, incarceration, or the end of a parent’s relationship. Even children with emotionally and financially stable family backgrounds may have experienced trauma from natural disasters, such as wildfires, the COVID-19 pandemic, or experienced frightening and painful medical or surgical procedures. All of these traumas may make it difficult for children to focus, create and maintain healthy relationships with peers and teachers, and meet classroom expectations.

| 1 | California County Superintendents Educational Services Association (2011). Transitional Kindergarten Planning Guide: A Resource for Administrators of California Public School Districts. p. 22. |

| 2 | Vygotsky, L.S. Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Mental Processes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA (1978). |

| 3 | Heritage, Margaret. Formative assessment: What do teachers need to know and do? Phi Delta Kappan, 89, No.2 (2007). |

| 4 | National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2009). Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Center on the Developing Child. Harvard University. Working paper 1. http://developingchild.harvard.edu/activities/council/ |

| 5 | National Center for Culturally Responsive Educational Systems. (Fall, 2005). Cultural considerations and challenges in response-to-intervention models: An NCCRESt position statement www.nccrest.org. |

| 6 | Siegler, R. S., & Alibali, M.W. (2005). Children’s Thinking (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. |